When I raise the topic in my seminars of making clear requests within intercultural business contexts, participants wonder at first what there is to say about something that seems so self evident. After all, everyone knows how to ask for what they want, don’t they, when speaking their native language? So why wouldn’t this also be true when using English as a second language? In theory this is true but in practice… not so much. I like to demonstrate this to my seminar participants by beginning with amusing examples of requests gone wrong, such as those that follow.

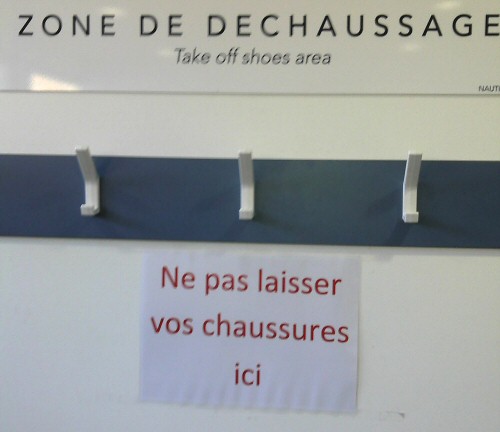

The image below is a sign that I saw the first time I went to the opening day of a health club located in Sophia Antipolis, close to where I now live. I noticed when I walked into the ‘Take off shoes area’ that some people were leaving their shoes in that room, under the benches. Others were carrying them to the change rooms. Since everyone had to walk through shallow water to get to the change room and pool area, leaving shoes on was not an option.

All around me, people who were also there for the first time were having conversations in a variety of languages: French, English, Russian, Italian and several others I couldn’t identify. The mix of languages was not surprising, since Sophia Antipolis is one of the most international areas of France – it hosts 30,000 people from more than 60 countries, working for over 1,000 companies. As I listened to people debating what to do, my thought was that the problem with the sign was that it was not making a request — it was stating a fact. This was indeed a room designated for taking your shoes off. A request was perhaps implicit but that obviously did not communicate effectively enough.

The next time I went to the club, I saw the improvised sign in the next photo, in French, under the original sign. In English it means, “Do not leave your shoes here.” Okay, that was at least a request. And there were fewer shoes left behind in the shoe room, compared to my last visit. However, I noticed this time that there were also more shoes left on the floor of the change room. Obviously, there was still confusion about what exactly club visitors were expected to do with their shoes.

A club employee finally found a solution to the miscommunication. The third time I went to the club, I saw this series of improvised signs placed on all four walls of the shoe room.

From left to right were these three requests: take off your shoes; carry them in your hands; and put them in your lockers. Finally, clear requests everyone could understand and follow — if they understood French, of course. However, since most of the people going to the club live in France full time, they obviously understood what to do, since there were now no shoes in the ‘Take off shoes area’ or in the change room. Finally, all shoes were in lockers, where the people who ran the club wanted them. So why hadn’t they just made a clear request in the beginning? Why did it take them several weeks to figure it out? This proves my point that making requests within intercultural contexts is not as evident as we may think.

Here’s another example, which I came across at a government agency for foreigners coming to France. It instructs peple to put out their cigarette in an ashtray, with an arrow pointing to it Here. In this second instance, many of the people going by that sign had little or no French language skills. So I guess the thinking was that a really gigantic arrow would communicate clearly where the officials wanted the cigarettes put out. The multiple burn marks on the arrow indicate otherwise.

In this second example I never actually saw anyone take the sign literally by putting out their cigarette on the arrow, since the metal ashtray below the arrow had evidently vanished long ago, leaving just a sad reminder of another failed, unclear request. So I have no way of knowing whether people were just doing it for a joke or were honestly trying to comply with what many of them must have thought was some sort of bizarre French custom of extinguishing cigarettes on big red arrows.

I hasten to add that these examples are not intended as a criticism of the French or their way of communicating. On the contrary, as I outline in more detail here, making unclear requests is a universal handicap that I have observed repeatedly over the decades of leading communication workshops with people from a variety of cultures.

These examples are intended instead to demonstrate that if such confusion can result from the simplest of requests, just imagine what happens in intercultural businesses around the world, in which countless, complex requests are made every day. How much chaos do unclear requests create? And how much lost time and revenue does this represent, not to mention frustration and mistrust?

The takeaway from all this? That all of us working within intercultural business contexts must relentlessly keep our listeners in mind. We need to let them know exactly what we are asking of them; only then can they choose to cooperate. Often we jump to the wrong conclusion that others are being difficult or uncooperative — when they may have simply misunderstood what we requested of them because we were not clear enough.

This is the year you have decided to become a more effective intercultural communicator? Bravo! You can purchase and download my eBook, along with an 80-page workbook. Not sure? Read a free extract. Questions? Just ask.